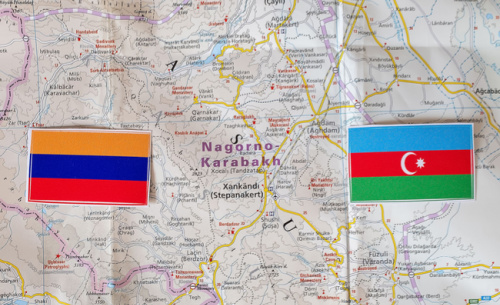

BACKGROUND: There is, as yet, no authoritative policy statement about the Caucasus from the Administration. However, heightened U.S. and European interest in helping create a genuine security order in the Caucasus will decidedly benefit the region and its neighbors. Hitherto Russia has possessed the exclusive great power presence here and the results of its policies now speak for themselves. Georgian politics have been corrupted leading to a loss of dynamism in the publicly supported drive to membership in Western security organizations. Moscow and its Georgian clients have steadfastly endeavored to bring it back into Russia’s economic-political orbit while detaching South Ossetia and Abkhazia from it de facto if not de jure. Russia has kept the tensions between Azerbaijan and Armenia boiling, selling arms to both sides and using its historical position as guarantor of Armenia to secure military bases there as an artifact of its regional hegemony.

However, since the Second Karabakh War of 2020, Russia has had to share its position with Azerbaijan’s ally Turkey. It has not challenged Turkish military support for Azerbaijan given the value of a working partnership with Ankara and suspicion of the Pashinyan government’s agenda in Armenia. Even though it inserted peace enforcement troops into the territories in dispute between Yerevan and Baku, Moscow may also have taken Armenia’s subordination to its will for granted since it seemingly had few other alternatives. Consequently Turkey is now a major military and economic presence in the Caucasus and uses that position as a springboard for significant economic power projection into Central Asia. Finally, since Russia invaded Ukraine, it has had to withdraw military and economic resources from the region, continued to refuse to counter Baku’s encroachments on Armenian territory, and sidestepped any disputes with Turkey.

The foregoing developments portend, as does the war with Ukraine, the dissolution of Russia’s imperial dream. The results of this gradual retraction of Russian economic-military-diplomatic power have had several notable consequences. Baku has gained a free hand to continue advancing against Armenia in its efforts to go beyond the November 2020 armistice to seize territories that will either pressure Armenia to accede to, or create, a land bridge to its Nakhichevan province. Russia has refrained from opposing these moves, clearly supported by Turkey, with deleterious outcomes for its standing in Armenia. Armenian public opinion has turned strongly anti-Russia, seeing it as a faithless and possibly retreating power. This reversal of public sentiment, in turn, opens the door to the EU and Washington to intervene diplomatically, offer their good offices and mediating capabilities to both sides, secure in the knowledge that Yerevan is receptive to their message.

Meanwhile Azerbaijan evidently does not wish to fight a war but simultaneously is exercising coercive diplomacy vis-à-vis Armenia to secure its territorial and commercial objectives at the latter’s expense, namely a trade route through the areas of southern Armenia that will connect it with Central Asia, China and at the other end Europe through Turkey. Enjoying Turkish support, Russian withdrawal, and Armenian weakness, it obviously believes the time is ripe to consolidate these gains before anyone can stop it. Yet its objectives also skirt the Armenian border with Iran, a factor that greatly antagonizes Iran and could add to the rest of the tense Irano-Azerbaijani bilateral agenda. Tehran views this as a “land grab” and as a threat to its ally, Armenia, and views Azerbaijan as an apostate, pro-Western Shiite state who threatens to generate another hostile military force, supported by the West, Israel, and Turkey and open the presence of those states’ militaries on its border. Furthermore, the long-lasting Iranian suspicion of Azerbaijani irredentism among Iran’s large Azerbaijani minority as a long-standing pretext for foreign intervention is a constant factor in these tense bilateral relations.

This “map” of the regional and international connections spawned by the war and the West’s negligent attitude towards making a sustained effort to resolve it since the 1990s underscores the potential inter-continental repercussions should Armenia and Azerbaijan come to blows again. But these factors, particularly Russia’s disengagement, also opens the way to a renewed and hopefully more sustained Western engagement in peacemaking.

IMPLICATIONS: These trends clearly owe much to the unforeseen development of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Moscow’s failure has heightened the importance of the Caucasus and potentially Central Asia as an alternative source of energy supply. The inherent dangers in Russian efforts to retrieve and sustain its hegemony throughout the former Soviet Union are now apparent to everyone in both European capitals and Washington. The corresponding decrease in Russian standing and capability has now generated opportunities for other actors to project their influence and power into these areas and also moved them to take advantage of such opportunities. Hence the signs of enhanced U.S. and European activity in both the Caucasus and Central Asia. These activities are not exclusively tied to getting more oil and gas from these areas as the Western mediation for the war over Nagorno-Karabakh shows.

U.S.-EU mediation reflects all these factors and the preconditions for its success can be compared to the Camp David and Dayton processes that fostered peace in the Middle East and in the Balkans respectively. Those initiatives succeeded both in terms of reaching an agreement and implementation because of persistent high-level engagement with the parties. Once EU engagement in the Western Balkans ebbed, so did the pressure for the parties to conform to these agreements with visible results to date.

Thus, should the parties reach an accord, the U.S. and EU need to sustain the process by the involvement over time of foreign ministers and heads of government. In the U.S., this means that Secretary Blinken, Vice-President Harris, and/or President Biden must make the Caucasus a priority and show up there to demonstrate the importance of this region to the U.S. These visits should go beyond existing regular diplomatic interchanges. This would be equally beneficial if they did so as well with regard to Central Asia, for example by convening a C5+1 meeting at the presidential level on the sidelines of the UN meeting in New York this fall. Likewise, their European counterparts should follow suit in both regions. Moreover, to oversee implementation it would be wise to designate a kind of high commissioner in both Washington and Brussels with wide powers and authority to coordinate all the bureaucracies involved and be in constant contact with all the parties.

Inasmuch as these negotiations will comprise borders, territorial delineation, security, trade routes, compensation of refugees on both sides, and the termination of all acts of belligerency by both governments, to make this process work the U.S. and Brussels must willingly accept that they will have to commit a sizable quantity of resources, economic, military, and political capital, for a long, possibly indefinite period of time. Such “side payments,” e.g. guaranteeing Israel’s oil supply from Egypt at Camp David and the placement of U.S. forces in the Sinai, are necessary. These forces must come from uninvolved players, have sufficient authority and numbers to act robustly if necessary, and enjoy equal credibility in Yerevan and Baku. Substantial funding, e.g. for refugee compensation, will also be necessary over time. Yet this investment in peace will be justified since peace will trigger major foreign and infrastructural investments in all three countries.

CONCLUSIONS: Crisis denotes both challenge and opportunity. In this case Western policymakers now have a once in a generation opportunity to launch and underwrite the most positive transformation of European and Eurasian security since the end of the Cold War, by laying the foundation for a new order in the Caucasus. Realizing this opportunity will not come cheap or without significant effort. However, the price of failure is still more excessive and long-lasting.

A Western-brokered peace will assist the peaceful dismantling of Russia’s imperial quest in the Caucasus and will forestall another round of war between Azerbaijan and Armenia while reducing the conflict potential between their major power sponsors, Turkey and Russia. It will also reduce the likelihood of Irano-Azerbaijani hostilities that would likely expand a conflict in the Caucasus to the Middle East. A Western-brokered peace will return both Azerbaijan and Armenia to their cultural homelands in the West and reduce Russian leverage in Georgia and regionally. It will also expand the economic horizons and relationship between the Caucasus and Central Asia, including the energy trade, thereby reducing Iranian and Russian efforts to prevent economic and energy contacts between these two regions and Europe. Similarly, lifting Turkey’s blockade of Armenia also allows for it to participate in emerging trade and transport initiatives connecting the Caucasus with the outside world. Armenia’s democratization program will also grow commensurately stronger with the coming of peace, which will unlock foreign investment and more direct support of that program. All these opportunities to bring the region and its neighbors into a virtuous circle now exist. If peace with all these ensuing benefits can be brought into existence, then we must seize the opportunity.

Stephen Blank is a Senior Fellow with the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Book S. Frederick Starr and Svante E. Cornell,

Book S. Frederick Starr and Svante E. Cornell,