BACKGROUND: On January 9, the Georgian government officially cancelled the 2016 agreement signed with the Anaklia Development Consortium (ADC). The official reason was ADC’s failure to follow the requirements present in the agreement. As a result, all the ongoing works in and around Anaklia stopped.

The ADC’s project to build a port in Anaklia was not the first such attempt. In fact, even during Soviet times, the Communists laid out a project to build a deep-sea port in Anaklia. However, the idea failed due to the USSR’s lack of resources and economic difficulties in the late 1980s and, as some observers believe, because Moscow did not want the first Soviet deep-sea port to be located on Georgian territory. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, despite Georgia’s internal instability and economic downturn of the 1990s, several projects were suggested for the port’s construction. After the 2003 Rose Revolution, a project called Lazika was introduced, which was nevertheless officially abandoned in 2012.

Thus, Georgia’s political elites have shared a clear understanding over time that the Anaklia port is crucial to Georgia’s economy and that it will benefit other states in the South Caucasus and the Caspian basin a well.

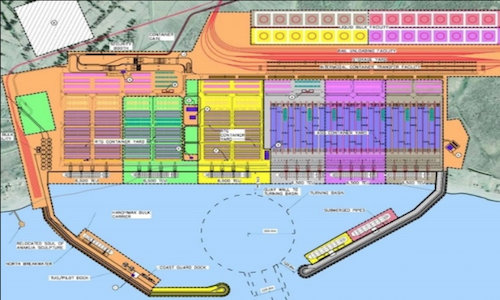

Large ocean-going freighters can easily enter the Black Sea, but can unload their cargo only in several ports located on the sea’s western shores. The eastern part of the Black Sea lacks deep-sea ports, which has constrained the development of economic relations in the region. The construction of the Anaklia port would allow the eastern half of the Black Sea Basin to host large Panamax vessels, which navigate the Panama and Suez Canals.

IMPLICATIONS: Many observers consider the Anaklia port as a purely economic project and have argued that it was undermined primarily by animosity between various leading political figures in Georgia. However, Georgia’s economic problems and regional geopolitics, primarily Russia’s tacit interest in derailing the project, are also important reasons for Anaklia’s failure.

In light of the growing railway and road infrastructure linking Georgia with Azerbaijan, the Anaklia port would allow the Caspian basin and the littoral Central Asian states to become more actively tied to the South Caucasus transport and energy corridor. This endows the project with a distinct geopolitical significance as it fits well into the U.S. and European efforts to build east-west transportation infrastructure in competition with Russia’s pursuit of north-east initiatives. Indeed, the Russian factor has been in play all along. Although Russian officials have voiced very few reactions to the Anaklia port, Moscow’s recent moves in the Black Sea nevertheless demonstrate how important it is for Russia to construct the first deep-sea port in the area. It was announced in mid-2019 that the RMP (RosMorPort) Taman Consortium, which includes five companies, will build the Taman Port. Located on the Russian side of the Kerch Strait connecting the Black and Azov seas, the port will likely undermine Anaklia’s potential as a transit between the Black and the Caspian seas and will become a primary focus for Panamax vessels in the eastern part of the Black Sea.

Another negative development for the Anaklia project comes from Georgia itself, which in 2019 made decisions to enlarge other Georgian ports. These include building a multimodal transit terminal in Poti and the invitation of several foreign companies to present their offers for this project. The Georgian government has also floated the idea of constructing an additional terminal in Batumi. Whereas neither of these ports are deep-sea, their expansion nevertheless limits Anaklia’s potential and raises questions regarding its efficiency.

However, there are also positive prospects for the construction of Anaklia. For Georgia, 2020 is a politically highly volatile period; the country will hold parliamentary elections that are in many ways decisive. The Anaklia project is guaranteed to be a hotly debated subject and a tool for various parties to direct recriminations against opponents. Therefore, internal Georgian politics could actually be a factor in keeping the idea of the port on the agenda. Indeed, Georgia’s Minister of Economy Natia Turnava has already announced a government tender in order to find new investors.

More importantly than Georgia’s internal politics, there is a larger, Eurasian dimension to Anaklia’s geopolitical significance, which will likely keep the project on the agendas of major regional actors. Although Beijing and Washington have recently made progress on trade issues, the geopolitical competition between the two is unlikely to decrease. In all likelihood, Washington’s imperative to limit Beijing’s expansion in the center of Eurasia will only grow stronger. One expression of this U.S. policy is to limit Chinese moves to acquire control of important infrastructure such as roads, ports and railways. As a strategically located port, Anaklia has become part of this competition, which was well reflected in U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s statement from June 2019: “[Anaklia’s] implementation will strengthen Georgia’s ties with free economies and will not allow Georgia to be under the economic influence of Russia or China. These imaginary friends are not driven by good intentions.”

As the U.S. and China have fundamentally different visions for the future modelling of Eurasia, it is frequently argued that this competition undermines the prospects for the construction of Anaklia. However, the same geopolitical struggle and the possibility that, after the latest unsuccessful attempt, Anaklia could fall into Chinese hands could in fact increase the U.S. interest in the port.

The significance of the Anaklia port in strategic U.S. interests has been reflected in various recent statements and political moves. For example, in several critical letters sent to the Georgian government, the U.S. Congress has urged Tbilisi to build Anaklia as it would improve the country’s position in the region. Moreover, the long-awaited new U.S. ambassador to Georgia, Kelly C. Degnan, is regarded by many in Tbilisi as a person specifically chosen to help Georgia’s political transition in 2020 and pay particular attention to the implementation of the Anaklia project.

CONCLUSIONS: Despite the failure to construct the Anaklia port due to regional geopolitics (Russian influence) and Georgia’s internal economic developments (expansion of the Batumi and Poti ports), there are larger geopolitical reasons, namely U.S.-China competition for Eurasian ports and other critical infrastructure, which increase the stakes for the U.S. regarding the construction of Anaklia.

Moreover, as the history of past and continually failing attempts to build a deep-sea port in Georgia shows, there is a clear understanding among the Georgian political elite on the need for a deep-sea port, which will increase Georgia’s economic and geopolitical importance in the Black Sea area. In fact, the construction of Anaklia relates strongly to Georgia’s westward ambitions including deeper economic cooperation with the EU and perhaps the use of Anaklia for military purposes, which will benefit Georgia’s cooperation with NATO.

Moreover, Anaklia might also become a game-changer in Georgia’s attempt to position itself as transit point between the Caspian and the Black Seas and further between Central Asian states and the European market.

AUTHOR'S BIO:

Emil Avdaliani teaches history and international relations at Tbilisi State University and Ilia State University. He has worked for various international consulting companies and currently publishes articles focused on military and political developments across the former Soviet space.

Image accessed on 3/6/20