Institutionalizing Central Asian Regional Cooperation

By Svante E. Cornell

In early August, Central Asian presidents met in Awaza in Turkmenistan along the sidelines of a UN conference, in preparation for their seventh formal consultative meeting, which will take place later this fall. The process of institutionalizing regional cooperation is progressing apace, as Central Asian cooperation has expanded from informal summits of presidents to a more formalized structure that is also branching out into meetings at the ministerial level and between representatives of parliaments. For the process to bear fruit, however, the Central Asian presidents will need to take more concrete steps to set up formal regional structures of cooperation.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

BACKGROUND: When Central Asian Presidents met in Awaza, Turkmenistan, on August 5 for a forum to prepare their more formal upcoming consultative meeting, it was difficult not to take a step back to note how different the situation is from only a decade ago. To begin with, until 2017, Central Asian leaders had met frequently in mechanisms involving other powers but rarely on their own. For years, they had built dialogue mechanisms with outside powers, Japan being the first to inaugurate a regional dialogue in 2004. The EU, the United States, and many others followed suit. But for close to a decade, Central Asian leaders did not have a regular format in which they met only as Central Asians, without foreign powers involved. Of course, this did not mean they had not met jointly for specific purposes, most notably the Treaty creating a Nuclear Free Zone for Central Asia, signed in Semey, Kazakhstan, in 2006.

Furthermore, the location of the meeting in Turkmenistan speaks volumes. During previous iterations of Central Asian efforts to build regional cooperation, Turkmenistan typically remained aloof, citing its permanent neutrality. The fact that Turkmenistan is now an avid participant in these efforts is truly a major development.

The rebirth of Central Asian regional cooperation got kick-started in 2017, when Kazakhstan’s then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev, responding to a suggestion by Uzbekistan’s new President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, convened a meeting of Central Asian Presidents. When this consultative meeting took place in 2018, it was the first time in almost a decade that Central Asian presidents had met without outsiders present. Since then, meetings between the presidents have taken place on a yearly basis.

The emphasis on presidential meetings is a reflection of the political realities of Central Asia. With political systems that are largely organized top-down, it is only natural that regional cooperation will be structured in a top-down manner, in the form of consultative meetings of the presidents. But for regional cooperation to be successful, it cannot only or even primarily be focused on presidential meetings. Quite to the contrary, regional cooperation will be successful when government agencies, trade councils, and civil society groups across the region cooperate in a structured manner with each other, through formal mechanisms or institutions.

Such a vision was launched at the fourth meeting of Presidents in Cholpon-Ata in 2022, where presidents approved a broad range of initiatives covering mutual relations in more than two dozen spheres, ranging from law, trade, sports, investment, visas, and education to security. Similarly, the 2024 sixth consultative meeting led to the adoption of a roadmap for the development of regional cooperation for 2025-2027 and an action plan for industrial cooperation among Central Asian states for the same time period.

IMPLICATIONS: More steps have been taken toward the building of institutions. Most importantly, the Presidents resolved at the 2023 Dushanbe Summit to establish a Council of National Coordinators of the presidential consultative meetings. Designed to “enhance the day-to-day effectiveness of interstate engagement and provide coherence to ongoing initiatives,” this body might in fact form the embryo of institutionalized Central Asian regional cooperation.

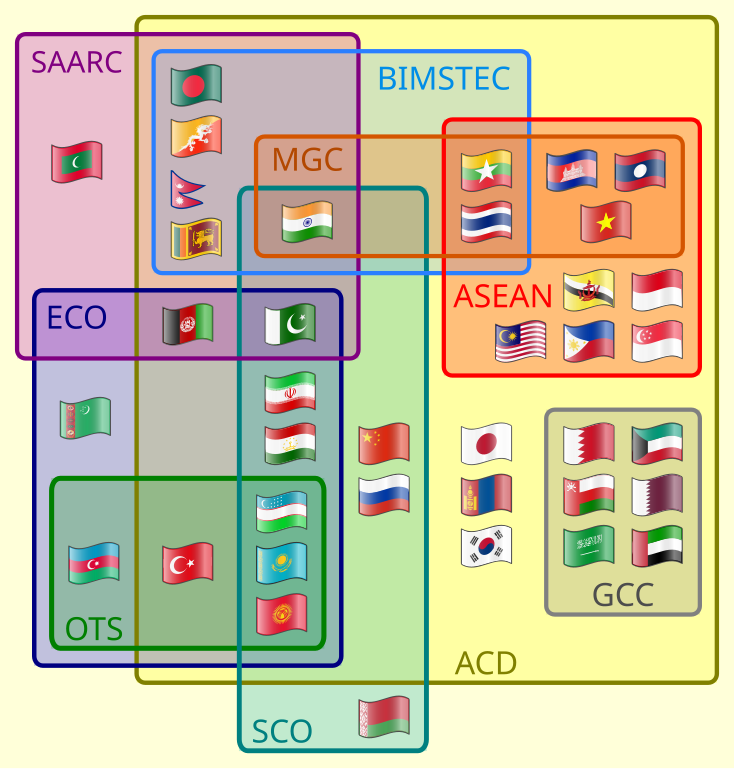

Further moves came at the 2024 summit in Astana, where the five presidents approved a strategic vision proposed by Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev entitled “Central Asia 2040”, subtitled a "Concept for the Development of Regional Cooperation." This strategic vision builds on President Tokayev’s concept of “Central Asian Renaissance,” outlined in a policy article published ahead of the 2024 summit. In this article, the Kazakh leader outlined a vision of a more integrated region that also serves as an interlocutor on the world stage with great powers and international organizations. As he points out, this is already beginning to take place as a result of deeper Central Asian coordination in multilateral bodies like the United Nations, as well as in organizations like the SCO in which Central Asian states are represented.

The “Central Asia 2040” document spelled out a vision to deepen integration in concrete areas like trade, energy, transport, environment, digital connectivity, but also specifically included the task of strengthening a joint Central Asian cultural identity. Beyond that, it mentions for the first time the institutionalization of meetings of heads of state into a formal regional structure. Accepting that the consultative meetings of Heads of State constitute “the cornerstone of political coordination,” it declares that this format is being institutionalized as a “permanent regional structure” and declares that it is being broadened beyond the Heads of State. It explicitly expands the formats of cooperation to include “parliaments, ministries, civil society, businesses, and think tanks.” It should be noted that minister-level dialogues are already underway: ahead of the 2024 consultative summit, there was a meeting of Central Asian transport ministers, as well as a meeting of energy ministers.

The five states have already initiated a movement to develop parliamentary cooperation. A first Central Asia Inter-Parliamentary Forum was held in Turkestan, Kazakhstan, in February 2023, and was followed by a second convocation in Khiva, Uzbekistan, in September 2024. Key matters discussed included cooperation on oversight over high-level agreements and the harmonization of legislation across Central Asia, as well as the development of a legal framework for a common economic space and for fostering cooperation in industry and transport.

In addition to these formal steps, informal contacts among government officials across Central Asia have increased exponentially over the past decade. Far from being isolated from each other as in the past or interacting only through formal means, representatives of Central Asian government agencies are now comparing notes and learning from each other in ways that were not imaginable a decade ago.

The development of Central Asia-wide regional institutions is thus a work in process, but that process will likely take time. To some degree, major decisions taken at the yearly consultative meetings continue to be determined by the lowest common denominator. It is well known that there are diverging levels of enthusiasm for how deep regional cooperation should be, a question that has been marring Central Asian regionalism from the start.

Turkmenistan and Tajikistan were long perceived as more skeptical to institutionalizing regional cooperation. But Turkmenistan’s hosting of the forum in Awaza shows its full participation in the process. And the recent progress in Kyrgyz-Tajik relations has also changed Dushanbe’s approach. When Kazakhstan’s suggestion for a friendship treaty among Central Asian states was raised at the 2022 Cholpon-Ata summit, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan refrained from signing. Tajikistan’s reticence could be attributed to its border conflict with Kyrgyzstan, which has since been resolved. Following the landmark Khujand Treaty of April 2025 that marked the resolution of the remaining border issues between the two countries, as well as Uzbekistan, Tajikistan’s President in late August signed the friendship treaty during a visit by Kazakhstan’s foreign minister Murat Nurtleu. It remains to be seen whether Turkmenistan will now also follow suit.

CONCLUSIONS: For Central Asian regional cooperation to be successful, it cannot long avoid speeding up the process of institutionalization. There is a limit to the momentum that can be achieved by pronouncements at the presidential level, even if those are followed up by ad hoc meetings at the ministerial level or between parliamentary representatives. Already, the implementation of the agreements reached at Consultative Summits is unclear. As the “low-hanging” fruit of easily achieved steps is picked off, achieving tangible results without regional structures will be increasingly difficult. For regional cooperation to be felt at the societal level and to become irreversible, structures of cooperation will be needed. That can ensure that presidential pronouncements are actually implemented at the national level. Furthermore, such regional structures can themselves identify and prioritize the main issues facing deeper regional cooperation in Central Asia.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Svante E. Cornell is Research Director of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Resolve Final Border Dispute: A Historic but Fragile Peace

By Aigerim Turgunbaeva

On March 31, the presidents of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan met in the Tajik city of Khujand to officially announce that all territorial disputes between their countries had been resolved. While future tensions cannot be ruled out, the region’s leaders now seem to believe that cooperation brings more benefits than conflict. For the Ferghana Valley, that shared outlook may be the strongest hope for lasting peace.

BACKGROUND: On March 13, Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov and Tajik President Emomali Rahmon signed a landmark treaty in Bishkek that definitively demarcates the entire 1,000-kilometer border between the two countries. The signing ended decades of intermittent clashes and unresolved territorial disputes rooted in the Soviet-era administrative boundaries. The agreement has been heralded as a major achievement in Central Asia’s regional integration efforts. Yet, the circumstances under which the deal was brokered—notably the lack of transparency, absence of public debate, and suppression of dissent—raise important questions about governance, public trust, and the future of cross-border relations.

The border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan has long been a source of friction, shaped by convoluted Soviet-era administrative divisions that ignored ethnic, geographic, and cultural realities. When both countries gained independence in 1991, these internal lines hardened into contested international borders. Enclaves, disputed villages, and overlapping claims turned the border zone—particularly Kyrgyzstan’s Batken region—into a hotbed of tension.As scholars have noted, Soviet planners in the 1920s and 1930s deliberately drew borders in ways that divided ethnic groups in order to weaken potential nationalist movements, creating enduring fault lines.

Violent clashes over land, roads, and water access occurred frequently, notably in 2014, 2021, and 2022. The 2022 conflict, which left more than 100 people dead and forced over 100,000 Kyrgyz citizens to flee their homes, was the deadliest to date. Civilian infrastructure, including schools and homes, was destroyed, exacerbating mistrust and trauma. Yet this tragedy also marked a turning point, prompting both governments to prioritize renewed negotiations. Talks resumed in late 2022 and intensified through 2023 and 2024, culminating in the March 2025 agreement.

Years of border-related violence left deep scars on both Kyrgyz and Tajik communities. Skirmishes often began with disputes over water access or road usage but escalated quickly due to the presence of military and paramilitary forces in civilian areas. Armed confrontations resulted in civilian casualties, displacement, and destruction of property. The 2021 and 2022 conflicts in particular revealed how unresolved borders and competing nationalist narratives can turn small incidents into full-scale battles.

These events created a humanitarian crisis, especially on the Kyrgyz side. Thousands were displaced multiple times, while cross-border trade and local economies ground to a halt. Despite multiple ceasefires and ad hoc agreements, durable peace remained elusive until the new treaty.

IMPLICATIONS: The treaty signed in Bishkek demarcates the full 972-kilometer boundary and resolves all outstanding territorial claims. While the full text of the agreement remains undisclosed, officials have confirmed that contentious zones like the Tajik exclave of Vorukh and surrounding Kyrgyz villages like Dostuk were key components of the deal. Reports suggest that land swaps and security guarantees played central roles in achieving consensus. Ceremonial gestures — including the reopening of checkpoints and reciprocal presidential visits — symbolized a new era of cooperation. Both governments framed the agreement as a diplomatic triumph.

The March 2025 agreement is notable not just for what it achieves, but how it came to be. After over three decades of deadlock, the treaty represents the first time that both governments have fully delineated and mutually accepted their shared border. While the specifics of the final map have not been made public, officials claim that all 972 kilometers have been agreed upon, including previously disputed enclaves and water-sharing arrangements.

Unlike past negotiations, which were often derailed by public outrage and nationalist pressures, the latest talks were conducted in near-total secrecy. Kyrgyz President Japarov pursued a top-down approach, sidelining parliamentary debate and civil society in favor of closed-door diplomacy with Dushanbe. Critics argue that this strategy undermined democratic oversight. At least two prominent Kyrgyz activists — including opposition figure Ravshan Jeenbekov — were detained for criticizing the deal and calling for public input on territorial concessions.

Despite these concerns, the breakthrough likely stemmed from a convergence of political incentives. For Japarov, resolving the border conflict bolsters his image as a strong and pragmatic leader, particularly after facing domestic backlash over economic stagnation and governance issues. For Rahmon, the agreement strengthens Tajikistan’s security and eases pressure on a regime that has faced increasing scrutiny over human rights abuses and political repression.

Moreover, international pressure and quiet diplomacy may have played a role. Both Russia and China—key players in the region—have interests in stabilizing Central Asia’s volatile borderlands. Beijing in particular has invested heavily in cross-border infrastructure and trade routes under its Belt and Road Initiative, and further conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan risked disrupting its regional ambitions. Despite both countries being CSTO members, Russia has kept its distance from the Kyrgyz-Tajik conflict. After invading Ukraine, Moscow lost interest in regional mediation. In October 2022, President Putin admitted Russia had “no intention of playing a mediating role,” offering only Soviet-era maps to aid negotiations. The Kremlin’s reluctance stems from earlier setbacks. A 2020 offer to mediate was met with a protest from Tajikistan, and Moscow’s failure to resolve the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict made it cautious about another potential diplomatic failure in its perceived sphere of influence. Russia’s limited role has highlighted Uzbekistan’s emergence as a key regional mediator. Since 2018, President Mirziyoyev has led efforts to revive regional dialogue through Central Asian summits without outside powers like Russia or China. By 2025, Tashkent had helped reopen communication between Rahmon and Japarov — who until recently would not even shake hands. Uzbekistan’s active diplomacy was especially visible in early 2025, when the prime ministers of all three countries met to discuss border issues.

The Kyrgyz-Tajik border accord could set a precedent for resolving similar disputes in Central Asia. Yet, the long-term success of the Kyrgyz-Tajik deal remains uncertain. Much depends on how the treaty is implemented on the ground. Villagers affected by the redrawn boundaries have voiced concerns about losing access to farmland, water sources, and ancestral homes. Without robust compensation mechanisms or inclusive dialogue, displaced or dissatisfied communities may become flashpoints for renewed tensions.

In Kyrgyzstan, the lack of transparency has already fueled public distrust. Some residents of Batken—the region most impacted by the deal—have protested what they see as the government’s unilateral ceding of territory without adequate consultation. Japarov’s administration has struggled to control the narrative, resorting to arrests and censorship to stifle dissent. If local grievances are ignored, the agreement could backfire, becoming a source of instability rather than peace.

Regionally, the agreement may also shift the balance of power. Tajikistan, a historically more authoritarian state, appears to have secured favorable terms in some contested areas, raising concerns in Kyrgyzstan about unequal negotiations.

Nonetheless, the border agreement represents a significant, if imperfect, step forward. It removes a major source of armed conflict, potentially allowing both governments to redirect resources toward economic development and infrastructure. It also provides a foundation for cross-border cooperation on water management, trade, and regional security, if both sides are willing to engage beyond security optics.

Whether this peace holds will depend not only on maps and treaties, but on how governments engage their citizens in building a shared future across once-divisive lines.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Aigerim Turgunbaeva is a journalist and researcher focusing on Central Asia. Aigerim writes about press freedom, human rights, and politics in the former Soviet space, and delves into China’s interests in the region for publications like The Diplomat, The Guardian, Reuters, Eurasianet.

A Greater Central Asia Strategy Without Russian Containment is Incomplete

By John DiPIrro

The Central Asia and Caucasus Institute’s proposed ‘American Strategy for Greater Central Asia’ (ASGCA) offers a timely recalibration of US engagement, centering on sovereignty, investment and regional interconnectivity. It challenges those of us steeped in democracy and governance work – that is, human rights, transparency, rule of law and institutional reform – to look beyond the normative ideals and confront the hard, often uncomfortable realities of power politics. It offers a serious and rare opportunity for the United States to redefine its role in a region that remains strategically vital and capitalize on a fleeting window of geopolitical advantage. Yet, without a robust policy of Russian containment, the strategy misses a key opportunity. To be effective, the US must help solidify a regional bulwark capable of resisting Russian military, economic and ideological coercion, while cultivating durable, mutually beneficial partnerships

BACKGROUND: For decades, U.S. engagement with Central Asia rested on flawed assumptions that development assistance, conditioned on commitments to democratic reform, would gradually yield stable, pro-Western partners. In reality, democratic reforms were largely performative and cosmetic, designed to appease U.S. interlocutors and secure continued funding. Russia and China, by contrast, offered a far more attractive alternative to Central Asian elites, including security guarantees, regime support, non-interference in internal affairs and tacit acceptance of corruption. These partnerships came with fewer conditions, demanding only loyalty.

Against this backdrop, the U.S. promise of prosperity through democratic transformation remained abstract and unconvincing in the face of authoritarian realpolitik. Even reformist leaders or color revolutions were quickly co-opted or violently displaced. In private, many regional elites sought a different offer: security, investment and recognition of sovereignty…without the "democracy business." Beijing and Moscow responded with infrastructure development and military cooperation, creating entrenched dependencies.

The Trump administration’s pivot toward transactional diplomacy that prioritizes economic and security partnerships over ideological demands has opened a window of opportunity to recalibrate U.S. engagement on terms regional governments find more palatable. Washington cannot and should not replicate the corrupt bargains offered by authoritarian powers, but it can offer something categorically superior: access to global markets, cutting-edge technologies, diversified security cooperation and entry into a predictable, rules-based order. This model, though imperfect, offers autonomy without the coercion, instability and dependency imposed by Moscow or Beijing. A pragmatic U.S. strategy grounded in sovereignty, prosperity and alignment could finally forge resilient and durable partnerships.

Meanwhile, Central Asia’s younger, urban, and globally connected populations are increasingly disillusioned with both domestic authoritarianism and foreign exploitation. Nationalist and pro-sovereignty sentiment has surged, particularly in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, its denial of Central Asian sovereignty and its mobilization of ethnic minorities into the Russian war effort have further fueled this backlash. Many citizens across the region have grown tired of being pawns in great-power rivalries.

It is within this context that the ASGCA represents a meaningful shift. By acknowledging regional priorities and accepting transactional diplomacy, it replaces Western idealism with strategic realism. ASGCA’s central innovation is its proposal to view these states not as isolated, vulnerable peripheries, but as a potential collective bloc, with Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan at its core, and Afghanistan, Mongolia and the South Caucasus anchoring each end. This corridor would align sovereign interests with US strategic goals and offer three critical advantages:

- Strategically, it would anchor a contiguous bloc that counters the Russia-China-Iran axis and dilutes their regional influence.

- Economically, it would unlock immense investment opportunities, from critical minerals and renewable energy, to trade corridors like the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (Middle Corridor), bypassing Russian chokepoints and providing an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

- In terms of security, it would foster regional self-sufficiency in counterterrorism, border control and internal stability, thereby reducing the need for US military presence. This feature aligns with both American and regional preferences.

Yet, ASGCA’s vision omits a crucial dimension. Without an explicit strategy for containing Russian influence, the project risks being strategically incoherent.

IMPLICATIONS: While international law affirms Russia’s 1991 borders,[1] the Kremlin’s own doctrine tells another story. The Russkiy Mir (Russian World) ideology, a cornerstone of Moscow’s aggressive expansionism, asserts a transnational Russian civilization that overrides international borders whenever it is politically expedient. Russia’s borders, in its own eyes, end only where they are met with sufficient resistance. This has become painfully clear since the 2008 invasion of Georgia, the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the 2022 full-scale war on Ukraine. The Kremlin’s disregard for sovereignty is not the exception: it is policy. This is why any peace settlement in Ukraine is likely to be tactical, not transformational. Moscow will use the opportunity to rearm and resume aggression when conditions are more favorable. As such, the West cannot afford another cycle of accommodation and illusion. A sustainable US strategy must empower regional actors to deter Russian pressure without direct American military deployment.

For this reason, any effort to unify and empower Greater Central Asia must explicitly incorporate Russian containment. By systematically investing in the region’s defense capabilities, economic integration and institutional resilience, the US can help Central Asia and the South Caucasus form a cohesive bloc capable of withstanding Russian pressure. These nations offer unique strategic value, including deep familiarity with Russian tactics, a pragmatic understanding of hard power and a growing desire to pursue independent paths. Unlike Western policymakers who often misread Moscow through a liberal, rational-actor lens, Central Asians and Caucasians harbor no such illusions, fully recognizing the necessity of strength and self-reliance.

Six reasons underscore this imperative.

First, without containment, sovereignty will remain fragile. Russian influence is not limited to tanks and troops. It manifests itself in cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, political subversion, cultural hegemony, economic blackmail and manipulation of ethnic minorities. In Kazakhstan, Russia’s rhetoric about “protecting Russians abroad” has stoked deep anxieties among political elites. In Armenia, Moscow’s failure to intervene during the 2023 Azerbaijani offensive exposed the hollowness of its security guarantees. If Greater Central Asia is to be more than a vision, it must be hardened against the hybrid Russian threats from the outset.

Second, containment is a precondition for regional integration. The Middle Corridor, a central component of ASGCA’s economic vision, cannot function without security. However, these corridors remain vulnerable to disruption without regional security guarantees. Russian influence over rail, road and energy infrastructure, particularly in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, makes any ambitious transit strategy susceptible to sabotage or political manipulation. A concerted effort to reduce Russian leverage is essential to ensuring the viability of east-west connectivity.

Third, Russia exploits regional divisions. Moscow excels at divide-and-rule tactics. It amplifies nationalist tensions, exacerbates border disputes and fuels distrust between neighbors. The longstanding water and border tensions between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan are fertile ground for Russian interference. A Greater Central Asia bloc must prioritize coordinated responses to hybrid threats, including joint intelligence sharing, cybersecurity collaboration and counter-disinformation mechanisms. Containment is not just a military goal. It is the precondition for durable regional unity. Geographically, this effort should concentrate along Russia’s southern flank, with the support of Turkey, India, Pakistan and the United States.

Fourth, U.S. credibility depends on strategic clarity and continuity. In Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, the West’s failure to provide hard security guarantees has had devastating consequences. Central Asian states have taken note. U.S. commitments must be unambiguous and they must endure beyond election cycles. If Washington abandons this strategy after four years, it will validate Russian and Chinese narratives about American unreliability and drive regional partners back into the arms of Moscow and Beijing.

Fifth, containment can be achieved without escalation. A containment strategy does not require US troops on the ground. Instead, it must empower local states to serve as their own first line of defense, resilient enough to resist Russian coercion. This includes arms transfers, defense cooperation, cybersecurity partnerships, sanctions enforcement and media resilience. It also means supporting sovereign decision-making and reducing dependence on Russian economic systems. Containment, if done smartly, is a stabilizing force, not a destabilizing one.

Sixth, a containment strategy accelerates the end of the Ukraine war. Central Asia and the South Caucasus are critical nodes in Russia’s sanctions evasion networks. Enforcing export controls, cutting off trans-shipment of dual-use goods and closing legal loopholes in countries like Kazakhstan, Armenia and Georgia would severely disrupt Russia’s war economy, hasten its operational exhaustion and enable a faster, more favorable resolution to the conflict. Building a coalition of states committed to rejecting Russian revisionism not only weakens the Kremlin. It also creates the conditions for an eventual peace on Ukrainian terms.

AUTHOR’S BIO: John DiPirro is a foreign policy and geopolitical risk expert focused on democracy, governance, conflict mitigation and strategic advocacy in the Caucasus, Central Asia and Eastern Europe. John spent the past 14 years leading democracy and political support programs across the Kyrgyz Republic and Georgia with the International Republican Institute.

[1] This excludes Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Abkhazia and South Ossetia as Russian territory.

China Remains Silent as Afghanistan-Pakistan Tensions Spiral

By Syed Fazl-e-Haider

At the conclusion of a five-day visit to China by Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari on February 8, China and Pakistan issued a joint statement urging the Taliban government to take decisive measures to eliminate all terrorist organizations operating within Afghanistan and to prevent the use of Afghan territory for hostile activities against other nations. Over the past three years, Islamabad has repeatedly accused the Taliban administration of providing refuge to the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a militant group responsible for attacks on Pakistani security forces and Chinese nationals within Pakistan. Despite being the largest foreign investor in both Pakistan and Afghanistan, China has thus far remained silent regarding the escalating tensions between the two neighboring countries. Meanwhile, Pakistan is poised to assert control over the Wakhan Corridor—a narrow strip of Afghan territory that extends to China's Xinjiang region, serving as a geographical buffer between Tajikistan and Pakistan. This corridor not only facilitates China's direct access to Afghanistan and Central Asia but also holds strategic significance, positioning it as a potential focal point in China's evolving geopolitical interests in the region.

Photo by Ninara.

BACKGROUND: The airstrikes conducted by Pakistan inside Afghanistan on December 24 heightened tensions between Islamabad and Kabul, leading to an increase in skirmishes along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Pakistan targeted TTP hideouts in Afghanistan’s Paktika province, resulting in the deaths of 46 individuals. In response, the Afghan Taliban launched retaliatory attacks on multiple locations along the Pakistan border, killing one Pakistani soldier.

This was not the first instance of Pakistan conducting airstrikes inside Afghanistan. In March 2024, Pakistani airstrikes targeted TTP bases within Afghan territory, resulting in the deaths of eight militants. The strikes occurred a day after President Asif Ali Zardari pledged retaliation following an attack by the TTP in Pakistan's northwestern tribal are bordering Afghanistan, which claimed the lives of seven soldiers, including two officers.

As tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan escalate and border clashes intensify, Pakistan is reportedly preparing to assert control over the Wakhan Corridor—a narrow strip of territory in Afghanistan's Badakhshan province that extends 350 kilometers to China's Xinjiang region, serving as a geographical buffer between Tajikistan to the north and Pakistan's Gilgit-Baltistan region. Control of Wakhan would provide Pakistan with direct access to Tajikistan, effectively bypassing Afghanistan. In this context, the visit of Pakistan’s top intelligence official to Tajikistan on December 30, 2024, holds particular significance. Tajikistan hosts the leadership of the anti-Taliban National Resistance Front (NRF) of Afghanistan. During his visit, the Director-General of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), General Asim Malik, met with Tajik President Emomali Rahmon in Dushanbe. The ISI chief is believed to have been on a strategic mission to establish an alliance with the NRF as a counterbalance against the Taliban.

China' has remained silent regarding the escalating tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Although a potential conflict between the two countries could jeopardize Chinese investments worth billions of U.S. dollars in both states, Beijing has opted for a "wait and watch" approach toward the ongoing hostilities. However, China is closely monitoring developments in the Wakhan Corridor, a strategically significant passage that provides direct access to Afghanistan and Central Asia.

On December 30, 2024, during the visit of Pakistan’s ISI chief to Dushanbe, China’s Ambassador to Kabul, Zhao Xing, was simultaneously meeting with Afghanistan’s acting Interior Minister, Sirajuddin Haqqani. This meeting took place amid media reports suggesting that Pakistan’s military was advancing to seize control of the Wakhan Corridor. Both sides emphasized the corridor’s strategic significance for bilateral trade. Taliban authorities dismissed claims regarding the presence of foreign (Pakistani) military forces in the corridor and pledged to address any security threats along Afghanistan’s borders. In September 2023, the Taliban government inaugurated a 50-kilometer road extending from the Wakhan Corridor to the Chinese border.

IMPLICATIONS: A key factor behind China’s silence on the escalating tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan is its own security concerns regarding Uyghur militancy in its Muslim-majority Xinjiang Autonomous Region, which shares a border with Afghanistan. The Taliban could potentially leverage the "Uyghur card" to destabilize Xinjiang, given that the previous Taliban regime (1996–2001) provided sanctuary to Uyghur militants in Afghanistan. The Taliban has issued a warning to Beijing against adopting a pro-Pakistan stance in the ongoing conflict, cautioning that Islamabad is attempting to draw China into its proxy war. China remains apprehensive that Uyghur jihadists could gain ideological and operational support under Taliban rule. Consequently, Beijing has consistently sought to avoid antagonizing the Taliban, opting instead for diplomatic engagement and substantial investments in Afghanistan’s energy, infrastructure and mining sectors following the US withdrawal from the war-torn country in 2021.

The Taliban’s warning to China came just days after China’s Special Envoy for Afghanistan, Yue Xiaoyong, visited Islamabad in November 2024 and stated that at least 20 militant groups were operating in Afghanistan, posing security threats to China.

Strategically positioned at the intersection of three major mountain ranges—the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Pamir—the Wakhan Corridor has the potential to become the focal point of China’s evolving geopolitical strategy in the region. At present, control over the Wakhan Corridor appears to be at the center of the geopolitical contest in Afghanistan, with Pakistan and Afghanistan seemingly acting as mere pawns in this larger game. As a silent yet influential player, China is subtly maneuvering these pawns on the regional chessboard.

Pakistan aligned itself with China’s broader ambitions to expand its influence across South and Central Asia through Afghanistan long before the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in 2021. However, rather than directly involving itself in the ongoing Pakistan-Afghanistan conflict, China appears committed to a strategy of cautious observation, continuously monitoring shifting geopolitical dynamics. Beijing seems to be waiting for an opportune moment to assert its influence.

For China, the Wakhan Corridor—often referred to as Afghanistan's "chicken neck"—serves as a crucial strategic node for establishing and securing connectivity with South and Central Asia through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This narrow strip of land has the potential to function as a pivotal junction, enabling China to expand its geopolitical and economic influence across the broader region.

However, security concerns remain a significant challenge in China's plans to extend the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship component of the BRI, into Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Several strategic projects planned or initiated by China align with its broader geopolitical strategy. One such initiative involves China's plans to establish a military base in Wakhan to bolster its counterinsurgency capabilities. China has already set up a military base in eastern Tajikistan, near the Wakhan Corridor. A military foothold in Wakhan would serve as a critical buffer, preventing terrorism and instability from spilling over from Afghanistan into China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region.

Additionally, China has constructed the Taxkorgan Airport on the Pamir Plateau in northwest Xinjiang, situated at an altitude of 3,258 meters and in close proximity of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. Beyond providing a new "air passage" that enhances connectivity between Central and South Asia, this ultra-high-altitude airport reinforces China's military and economic influence in the region.

While Beijing continues to invest in Afghanistan—despite its global isolation and international sanctions—it is simultaneously financing multiple projects under the US$ 62 billion CPEC in Pakistan. However, despite its deep economic and strategic engagements in both countries, China has remained silent regarding the escalating armed confrontations along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

CONCLUSION: China should take an active role in mediating the Pakistan-Afghanistan conflict rather than attempting to balance its interests with both sides. Leveraging its influence over both states, Beijing can push for diplomatic negotiations to address their disputes. At present, neither Islamabad nor Kabul is in a position to disregard China's calls for restraint, making it a crucial player in de-escalating tensions and ensuring regional stability.

China should take a definitive stance and clarify its official position on the TTP, which has been responsible for attacks on Chinese nationals and security forces in Pakistan. Beijing should deliver an unequivocal message to Kabul, asserting that if the Taliban government fails to dismantle terrorist networks operating from Afghan territory, China will align with Pakistan in conducting targeted airstrikes against anti-China militant hideouts within Afghanistan.

While China has remained silent on escalating Pakistan-Afghanistan tensions, the U.S. has endorsed Pakistan’s stance regarding the Taliban’s policy of sheltering terrorist groups, which violates the U.S.-Taliban Doha Accord. The withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan in 2021 enabled the TTP to operate with greater impunity. For Islamabad, the Afghan endgame has effectively become a zero-sum game. In response, some factions within Pakistan have advocated for collaboration with the U.S. to carry out airstrikes targeting terrorist hideouts inside Afghanistan.

AUTHOR BIO: Syed Fazl-e-Haider is a Karachi-based analyst at the Wikistrat. He is a freelance columnist and the author of several books. He has contributed articles and analysis to a range of publications. He is a regular contributor to Eurasia Daily Monitor of Jamestown Foundation. Email, This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .