The Middle Corridor Remains Supplementary to Major Trade Routes between the EU and China

By Emil Avdaliani

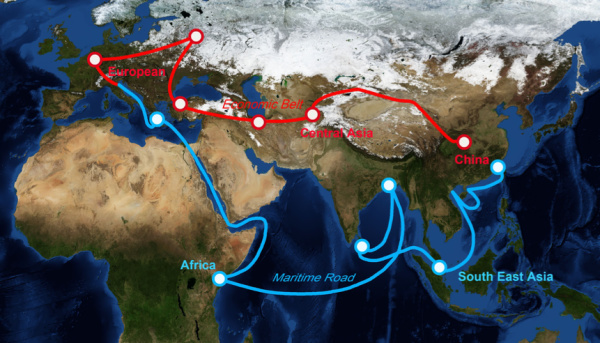

Although the Middle Corridor, connecting the EU and China via the Black Sea and Central Asia, has witnessed notable development in recent years, its swift expansion is constrained by both geographical barriers and the political complexities prevalent along the route. The Northern Corridor through Russia would be further consolidated should Russia achieve a favorable resolution to its war in Ukraine. While the Middle Corridor serves as a dependable link between Central Asia and the EU, it is likely to remain a complementary route to the northern Eurasian commercial highway.

Photo source: Tanvir Anjum Adib

BACKGROUND: The Middle Corridor, also known as the Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor, extending from the Black Sea to Central Asia and western China, has gained prominence since 2022 following the onset of the war in Ukraine. Although the route had existed in practice since the 1990s and was formally inaugurated in the early 2000s, its scope remained limited due to inadequate infrastructure, geopolitical instability in the South Caucasus, and, more significantly, the appeal of the Russian route, which had facilitated trade between China and the EU. Compounding these challenges is the corridor’s multimodal nature—comprising both land and sea segments—which, despite making it the shortest geographical path between China and the EU, has ultimately rendered its operation economically unviable.

Indeed, data from the period prior to 2022 highlights this unfavorable reality: merely 2–3 percent of overland containerized freight traversed the Middle Corridor. This dynamic shifted following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as the route became increasingly associated with geopolitical volatility, the unpredictability of Moscow, and the risk of financial loss for both the EU and China. In addition, the European Union’s imposition of extensive sanctions on Russia has further incentivized the pursuit of alternative transport corridors.

Overall, cargo traffic along the Middle Corridor increased in 2024 for railway operators in Georgia, Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan. For example, Azerbaijani authorities reported transporting over 18.5 million tons of goods in 2024, representing a 5.7 percent increase compared to 2023. In the case of Kazakhstan’s railways, the volume of freight carried via the corridor grew by 63 percent, reaching 4.1 million tons in 2024. Turkish and Georgian railway companies likewise experienced a rise in cargo throughput during the same year.

In late 2024, Kazakhstan unveiled plans to finance the construction of a new terminal at Azerbaijan’s Alat port. Concurrently, Astana is undertaking development efforts at the Aktau port, with authorities aiming to triple container throughput by the end of the decade. Additional recent developments similarly suggest a significant reorientation of strategic focus toward the corridor. Notably, in March, Azerbaijan hosted 24 companies for the General Assembly of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route International Association (TITR IA) Legal Entities Union. The objective of the assembly was to raise cargo volumes along the Middle Corridor to 96,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs).

IMPLICATIONS: Thus far, the outlook for the Middle Corridor has appeared favorable. Major powers are increasingly expressing interest in the corridor’s development. In early April, the inaugural Central Asia–EU Summit was convened in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. The event was viewed as an effort to enhance the European Union’s presence in the region amid intensifying great power rivalry over Eurasian connectivity. The EU pledged a €12 billion assistance package, of which €3 billion will be allocated to the transport sector. Central Asia holds strategic significance for the EU, particularly considering the Middle Corridor’s advancement within the scope of Brussels’ Global Gateway initiative—a rival to China’s expansive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). With improved transport infrastructure, cargo delivery times between Europe and Central Asia are projected to be halved, reaching approximately 15 days.

China is another major stakeholder, whose growing interest in the Middle Corridor is evident through both political engagement and investment initiatives. A Chinese firm is currently constructing a deep-sea port in Anaklia on Georgia’s Black Sea coast, a development that may prove instrumental in achieving the goal of capturing a 20 percent share of EU–China maritime trade by 2035. Previous efforts to build the port were hindered by domestic political disputes, but the present geopolitical environment differs, with China now actively supporting the project. Beijing has also sought to strengthen its political relationship with Georgia, culminating in the signing of a strategic partnership agreement in 2023. A similar agreement was concluded with Azerbaijan in 2024, with an upgraded version on April 23, 2025, in which China committed to enhancing the country’s Caspian Sea ports and advancing the long-delayed China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway. These developments collectively signal the emergence of a near-continuous corridor stretching from China’s western frontier to the Black Sea.

However, given the evolving geopolitical dynamics surrounding Ukraine—particularly the ongoing negotiations between Russia and the U.S.—the Middle Corridor may face adverse consequences. Should Russia secure substantial gains in Ukraine, its strategic influence in the South Caucasus is likely to be enhanced. This could result in the consolidation of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan within Moscow’s sphere of influence, thereby empowering Russia to obstruct the functioning of a transit route that circumvents its territory from the south and facilitates access for rival powers into Central Asia. Potential measures at Russia’s disposal span from overt military actions to more subtle strategies, including embedding itself economically through infrastructure investments in the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

Moreover, despite the war in Ukraine entering its fourth consecutive year, this has not signaled the complete demise of the Russian route. Indeed, between 2022 and 2024, the northern corridor has continued to function as a major conduit between China and the EU. While the volume of freight transported along this route has fluctuated, it has nonetheless persisted as a vital commercial artery. Consequently, the Middle Corridor has continued to serve in a primarily complementary capacity.

This underscores the enduring viability of the northern route and should Russia–U.S. relations experience a substantial improvement; major enterprises may increasingly favor the well-established northern corridor. In contrast, the Middle Corridor continues to face constraints arising from both geographic challenges and the involvement of multiple stakeholders along its path. Infrastructure remains underdeveloped, and while intergovernmental cooperation is progressing, it still falls short of what is necessary. The true potential of the Middle Corridor is projected to reach up to 20 percent of overland containerized trade between China and the EU. However, this estimate is conditional upon several factors, including the successful completion of the Anaklia port and the expansion of the railway network across the South Caucasus.

CONCLUSION: Although the Middle Corridor has experienced considerable growth in recent years, its overall potential remains constrained. Geographic limitations, combined with persistent political complexities along the route, continue to impede rapid development. However, broader shifts in Eurasian geopolitics pose even greater challenges—should Russia succeed in concluding the war in Ukraine favorably and reconciling with the U.S., the corridor traversing Russian territory would be further solidified. This scenario does not imply that the Middle Corridor will cease to evolve. Rather, it is expected to continue expanding while remaining complementary to the northern Eurasian trade axis and functioning as a reliable conduit between Central Asia and the EU.

AUTHOR BIO: Emil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at the European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of Silk Roads. He can be reached on Twitter/X at @emilavdaliani.

The Middle Corridor and the Russia-Ukraine War: the Rise of New Regional Collaboration in Eurasia?

By Selçuk Çolakoğlu

January 31, 2023

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the West‑led sanctions regime against Russia, coupled with Russian counter-sanctions, has affected everything from energy resources and logistics to banking transactions and customs procedures. Western countries have realized that Moscow can weaponize its geopolitical position and logistic networks. Strategic over‑dependence on Russia’s energy, markets, and logistics has created significant challenges to neighboring countries due to increasing political tensions between the West and Russia. This development is undermining the Northern (Russian) Corridor’s position as the main overland East-West corridor. In turn, the alternative Middle Corridor is currently facing its best opportunity ever to take a leading position in connecting Europe and Asia.

Russia-Kazakhstan dynamic in the context of European energy and economic security

By Mamuka Tsereteli

August 11, 2022

Kazakhstan, and Central Asia in general, needs a long-term energy and commodity export strategy. Economic and energy security for the landlocked countries requires diversification of the transportation options for export and import. Europe will need every extra barrel of oil it can get, and Kazakhstan needs reliable markets, so uninterrupted access to resources and markets through trusted connectivity with the likeminded countries should always be the priority in all times, good and bad.