BACKGROUND: The Caspian Sea is the world’s largest inland body of water, variably described as the world’s largest lake or a full-fledged sea and is shared between Iran, Russia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. The Caspian is connected to open waters through the Volga River and Volga-Don Canal. In recent years, several reports have been published regarding the decrease in the water level of the Caspian Sea. According to one estimate, Caspian water levels could drop by 9 to 18 meters (30 to 60 feet) by the end of the 21st century, thus losing about a quarter of its area and uncovering about 93,000 square kilometers (36,000 square miles) of dry land – an area roughly the size of Portugal.

In recent months, Iranian officials have warned several times of the negative consequences and according to Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Ecology, “the area of the body water declined by more than 22,000 square kilometers, and over a half of them belong to the Kazakhstan section of Northern Caspian Sea.”

There are two main reasons for the decreasing water level of the Caspian Sea. The first factor is climate change including warming, absence of precipitation and increasing evaporation from the Caspian Sea. Sea levels are rising due to global warming in many parts of the world, however, scientists note that warming and increased evaporation are likely to play out differently for inland seas and lakes. In the case of the Caspian Sea (technically a lake), scientists anticipate rapid declines in water levels in the coming decades and centuries, since evaporation is not balanced by either river discharge or precipitation.

The second factor is Russia’s construction of dams on the Volga River and the reduction of water entering the Caspian Sea. About 130 rivers flow into the Caspian Sea, however, in the “upstream” of this lake about 80 percent of the water comes from the Volga River, the longest river in Europe, while the Ural and the other Russian rivers play an important secondary role. In recent years, Russia has built 40 dams on the Volga River and 18 more dams are under study and construction. This has reduced the flow of water entering the Caspian Sea. Moreover, the war in Ukraine and Western sanctions against Russia have led to a sharp decrease in the import of agricultural products from Europe and the U.S. This has increased the exploitation of Volga water resources for the development of agriculture, especially wheat cultivation, in the surrounding areas of this river. According to a Kazakh expert, Russia’s intensifying use of upstream water hastens the rapid decline of the northeastern Caspian, which is also the location of Kazakhstan’s economically vital Kashagan oil field.

Indeed, despite the increasing alignment between Tehran and Moscow after the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Iranian officials blame Russia for the rapid drop in Caspian water levels. Ali Salajegheh, Iran’s Vice President and Head of Iran’s Department of Environment voiced the hitherto most outspoken criticism in August 2023: “water inflows, especially the one through the Volga River, into the Caspian Sea have been blocked by the neighboring countries. We hope to be able to settle the issues of the water rights and contamination within the framework of the Tehran Convention.”

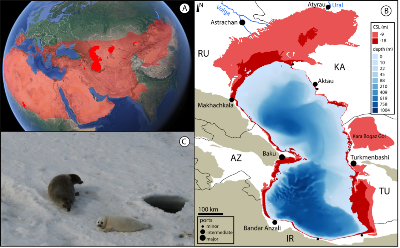

IMPLICATIONS: The Caspian Sea’s decreasing water level has several important implications. In the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea from August 2018, the water level was determined to be -28, meaning 28 meters lower than the water level of the oceans and open seas (relative to that of the Baltic Sea, which is used as a reference point to measure fluctuations in the Caspian water level). The current water level has reached -29 meters. This decrease can affect the determination of the “baseline,” which forms the basis for defining the scope of “internal waters”, “territorial waters”, “fishery zones”, “common maritime space” and “sectors.” The decreasing water level increases the area of land and beaches of all Caspian coastal countries. However, the advancing coast is larger in the upstream countries Kazakhstan and Russia, than in Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Iran.

Due to technical, geographical and legal complications, the “baseline” is not specified in the Caspian Sea Convention, where it was decided that “the methodology for establishing straight baselines shall be determined in a separate agreement among all the Parties.” Technical and expert negotiations on determining the baselines have been ongoing for over four years and have yet to be concluded. Therefore, the decreasing water level could lead to changes and amendments in the designated points of the “baseline” by Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan and affect the process of final agreements with Iran.

The decreasing water level in the Caspian Sea and the advancing coast will also have a negative impact on ports and docks as well as transit and shipping, especially along the coasts of Kazakhstan and Russia as two “upstream countries.” It will become difficult for ships to dock in the ports of Aktau, Quryq (Kuryk) and Atyrau in Kazakhstan and the ports of Astrakhan and Makhachkala in Russia. Moreover, most of the Volga River’s channels have not been repaired or even dredged since the fall of the Soviet Union, increasing the risk of serious accidents and making portions of the river impassable for all vessels, except the smallest and lightest. The severe lack of dredging has made the waters shallower, which has increased the difficulty of moving ships through the Volga and Volga-Don Canal. It is clear that the decrease in the water level of the Volga River and the Caspian Sea will aggravate these problems.

Decreasing water levels also poses challenges and threats to the ecosystem and environment of the Caspian Sea, particularly in coastal areas. Indeed, if the northern part of the Caspian, whose shallow waters have a rich fauna, would dry up, this would have major ecological consequences. It could also threaten protected areas and wetlands such as the Volga Delta in Russia and the Gulf of Gorgan (the largest gulf in the Caspian Sea) and Miankala Lagoon on the south-eastern shore in Iran. Also, the drying of wetlands and the advance of the coast can lead to the production of dust and affect the weather of coastal countries.

The process will also have a human and social impact. Ecological changes can lead to migration and population decline in coastal cities and villages around the Caspian Sea. The experience of the drying Aral Sea clearly shows the potentially significant human and social consequences of ecological changes.

CONCLUSIONS: These potential consequences are current and short-term. Yet the long-term effects and results of this process give rise to an even larger concern. The Caspian Sea level is projected to fall by 9–18 meters in medium to high emissions scenarios until the end of this century, caused by a substantial increase in lake evaporation that is not balanced by increasing river discharge or precipitation. The ecological results would clearly be disastrous.

According to Nature, “a decline by 9–18 meters will mean that the vast northern Caspian shelf, the Turkmen shelf in the southeast, and all coastal areas in the middle and southern Caspian Sea emerge from under the sea surface. In addition, the Kara-Bogaz-Gol Bay on the eastern margin will be completely desiccated. Overall, the Caspian Sea’s surface area will shrink by 23 percent for a 9 meter and by 34 percent for an 18 meter drop of sea level.” To overcome this very serious challenge, Caspian coastal countries should put integrated, coordinated and comprehensive policies and approaches on the agenda. In this process, it is very important to maintain and continue the flow of water from the rivers, especially the Volga to the Caspian Sea. This could compensate for an share of climate change losses such as air warming, sea water evaporation and precipitation reduction.

About the author: Vali Kaleji, based in in Tehran, Iran, holds a Ph.D. in Regional Studies, Central Asia and Caucasian Studies. He has published numerous analytical articles on Eurasian issues for the Eurasia Daily Monitor, the Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, The Middle East Institute and the Valdai Club. He can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .