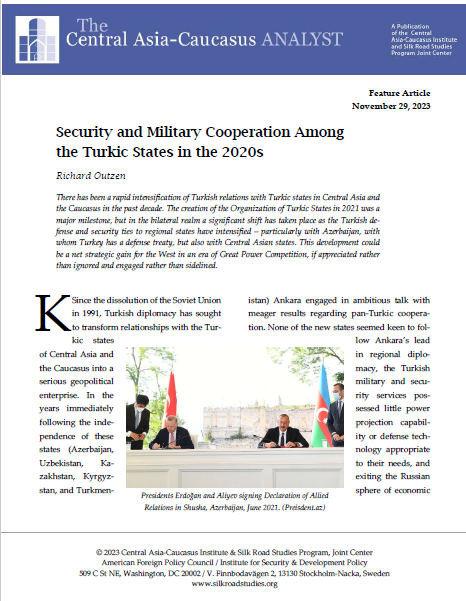

Security and Military Cooperation Among the Turkic States in the 2020s

Richard Outzen

December 8, 2023

There has been a rapid intensification of Turkish relations with Turkic states in Central Asia and the Caucasus in the past decade. The creation of the Organization of Turkic States in 2021 was a major milestone, but in the bilateral realm a significant shift has taken place as the Turkish defense and security ties to regional states have intensified – particularly with Azerbaijan, with whom Turkey has a defense treaty, but also with Central Asian states. This development could be a net strategic gain for the West in an era of Great Power Competition, if appreciated rather than ignored and engaged rather than sidelined.

Chessboard No More: the Rise of Central Asia’s International Agency

By Svante E. Cornell and S. Frederick Starr

October 3, 2023

Central Asia is often portrayed through metaphors such as a “Grand Chessboard” or a “Great Game,” which suggest that the players in the game are the great powers, and the Central Asian states are merely pawns in this game. This might have been a plausible argument thirty years ago. But today, thirty years into independence, it is abundantly clear that Central Asian states have agency at the regional and even global level.

Four Years On: An Update on Kazakhstan’s Reforms

Svante E. Cornell

October 24, 2023

Almost four years have passed since President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev embarked upon an agenda to bring thorough reforms to Kazakhstan’s politics and society. This article looks at the process of implementation of these reforms in a highly precarious geopolitical environment, where Russia’s war in Ukraine has led to increasing threats to Kazakhstan’s integrity by leading Russian figures. This analysis shows that Kazakhstan has proceeded on institutional reform, including modest but meaningful steps in sensitive areas such as separation of powers and electoral systems.

A New Spring for Caspian Transit and Trade

Svante E. Cornell and Brenda Shaffer

October 17, 2023

Major recent shifts, starting with the Taliban victory in Afghanistan and Russia’s war in Ukraine have led to a resurgence of the Trans-Caspian transportation corridor. This corridor, envisioned in the 1990s, has been slow to come to fruition, but has now suddenly found much- needed support. The obstacles to a rapid expansion of the corridor’s capacity are nevertheless considerable, given the underinvestment in its capacity over many years.

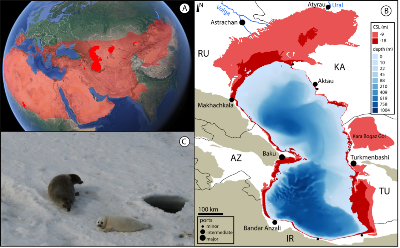

Decreasing Water Levels in the Caspian Sea: Causes and Implications

By Vali Kaleji

October 13, 2023

Various reports indicate that the water level of the Caspian Sea has decreased by one meter in recent years and could drop by 9 to 18 meters (30 to 59 feet) by the end of the 21st century. Although climate change contributes to this process, Russia’s construction of dams on the Volga River has played an important role in reducing the amount of water entering the Caspian Sea. This will have significant and serious implications, including a decline of the sea water level, a considerable retreat of the sea and increase of the land and coastal area especially in upstream countries (Russia and Kazakhstan), challenges to the operation of ports and shipping, as well as environmental consequences, particularly the drying of protected areas and wetlands.

Book S. Frederick Starr and Svante E. Cornell,

Book S. Frederick Starr and Svante E. Cornell,